Political journey

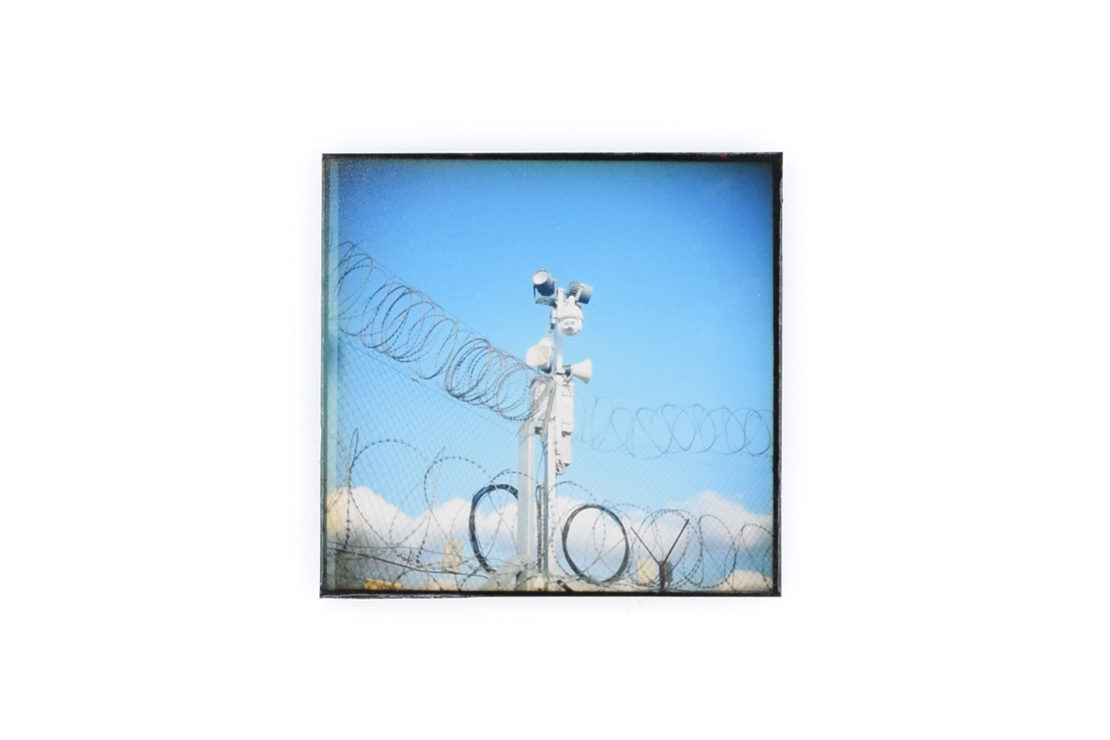

While border fences are a means of subjective, visible violence, passport controls at EU borders are an expression of objective and systemic violence.

Dani Ploeger im Interview

Do you also have positive travel memories from your journeys in border areas?

Yes, frequently. Last October, I met friendly wisents in the jungle on the Polish-Belarusian border. I made a clandestine foot journey across the forest to its geographic midpoint, which was calculated by a mathematician for my work A New Middle of Nowhere. Fortunately, it wasn’t until after the trip that I learned that wisents aren’t always so shy and regularly attack people in the region.

In 2019, after I installed my work OUR VALUES – which is now part of the exhibition – at the Hungarian border fence in Serbia, a young man came walking up to me from afar. It turned out that he was Tunisian and intended to cross the border fence in his summer clothes and without any tools. He agreed that it would be better to go eat something together first in the nearby town. There, he considered a safer and better prepared way to cross the border.

How does it feel to be allowed to cross borders where others fail?

The barriers that are often erected on border routes away from official crossings are hardly noticed by people with privileged documents – like me – while travelling and they are never physically encountered. Since I have started to engage with this topic more intensively, I experience the seemingly clean and peaceful border posts I pass through more and more often as another side of the same story. Seen from the perspective of Slavoj Zizek’s reflections on violence, one could say that the aspect of physical violence of the fences is a form of subjective, apparent violence, while the seeming cleanliness and peacefulness of the passport control zones for EU citizens is an expression of objective, systematic violence. Subjective and objective violence are dialectically connected, one works with – and because of – the other.

You travel solely by train. Why?

I work in the Middle East and Africa from time to time as well and then I travel by plane, but within Europe I travel almost exclusively by train. For me, the experience of the journey itself is important, especially in terms of the changing landscape, the architecture, and the interactions with people, even the seemingly unimportant encounters like with the employee in the train restaurant or a passerby at a transfer station.

The problem with travelling by plane is not only that it’s dirty, but also fleeting. These days, flying as an experience is increasingly shaped as a necessary step to reach one’s destination, which should be done as quickly as possible and preferably not even consciously experienced. In that sense, I think flying has become a form of ‘trash time’, in reference to architect Rem Koolhaas’ term ‘junk space’. Where Koolhaas describes a design of public spaces that only aims to increase consumption rather than provide a valuable experience in itself, I see the design of air travel today as a method of creating a kind of non-time, creating the illusion for travelers that the world is one big urban entertainment spectacle without areas of transition and socio-cultural distance.

Take us on your next journey. What do we see?

A lonely bulldozer is driving on an enormous sand plane. The driver has been tasked with using GPS navigation to erase and flatten everything within a square of 100 x 100 meters. A drone documents the bulldozer from the air while I film it from the side.

Next month I will produce a new work for the Kuwait Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, marking the 30th anniversary of the Gulf War. The war became known as ‘The First Space War’ because of the prominent role of satellite navigation. However, at the same time, there were troubling low-tech elements of the war that remained largely unreported in news media. US Army bulldozers were used as an assault weapon on the front lines. For my work A Space War Monument, a GPS bulldozer – a symbiosis of two prominent Gulf War technologies – is used to erase remaining traces of the war in the Arabian Desert.

In the 1990s, Jean Baudrillard claimed that the Gulf War had not really taken place because the vast majority of people had only seen representations of violence in the media, for which it was not clear whether they were related to actual events of the war or were merely simulations. In the same way, it will remain unclear in my work where the sandy area I traveled to is located exactly and in what form the work exists.

Exhibition

Bon Voyage!

Reisen in der Kunst der Gegenwart

13. November 2020 – 16. May 2021