Journey of discovery

Perhaps, in the end, the most essential meaning of all travel is to see the near with new or different eyes.

Interview with Timm Ulrichs

What significance does travel have for you and your work?

First of all: Basically, one has to admit that the Ludwig Forum has succeeded in creating the exhibition of the hour, indeed of the year, with “Bon Voyage!”, since the title seems like an ironic allusion to the “lockdown” to which the acute pandemic is forcing us. But it also proves the need, the necessity of man to move and to change places. We now notice how difficult it is to bear when the urge to move and freedom of movement are restricted; the general physical near-stasis also transfers to the mental and spiritual. Blaise Pascal already remarked on this in 1620: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.“ Although I have never owned a driver’s license or a car, I still travel quite a lot, by train or – in Berlin, Hanover or Münster – on one of my three bicycles. As a teenager, I was often on the road with my boy’s bicycle (without gears!), cycled from Bremen to Paris, in two days to Berlin or to Kleinwalsertal, and travelled often as a hitchhiker; but I haven’t been going on vacation for decades. I’m more inclined to thought expeditions than to physical travel from A to B, which can only be a good thing considering the state of the world and the environment. But when I do have to travel, equipped with a BahnCard 100, I like to sit in the dining car and enjoy the change of scenery, though almost exclusively within our national borders, since I have been able to find few performance opportunities abroad for myself and my art. On the other hand, I suppose that in the sixty years of my artistic work I have already visited almost every German town with more than thirty thousand inhabitants – including Aachen on several occasions. Literature and music can easily be conveyed immaterially, virtually and digitally; visual art, on the other hand, will probably continue to be shown primarily in analog form, in physical presence, and therefore there will be a continuous need to send its authors and works on travels materially, physically. (The fact that the immaterial, the physically insubstantial does not satiate is most beautifully proven by the story of the pre-conceptual artist Till Eulenspiegel, who in 1515/19 paid for the smell of roasting in an inn with the sound of money).

Which is more beautiful for you – going or arriving?

I don’t like to play one off against the other – both actually belong together, with the states of mind and temper associated with each. The beginning of a journey – whether a mental or a physical one – is determined by preparations and planning, anticipation, excitement and expectation, also uncertainties and imponderables of all kinds, up to the possibility of failure. The execution of the journey and the arrival at the destination are then, so to speak, the test of example and thought experiment; the before of the mood of departure then turns in the best case into pleasant exhaustion and relaxation, into recovery and enjoyment of the after. For me, the early planning phase, the making of plans, the finding and inventing, the thinking up and developing of ideas is the more important part, even if I also consider the execution of my works and the presentation of the results – which I equate with the arrival – to be significant. You need a lofty goal if you want to be a pathfinder and pioneer and win new ground; the maxim “Look for the stars! Pay attention to the alleys!” (Wilhelm Raabe, “Die Leute aus dem Walde”, 1862) is a good guiding principle for me, always more groundbreaking than the alleged Confucius quote “The way is the goal”.

Who travels more – you or your art?

As I said, I hardly ever travel for recreation or vacation, but I do travel for lectures or so-called business trips and art transportation for installing my exhibitions and for opening events, as well as routine trips between my three work locations in Hanover, Berlin and Münster, which is possible within four hours. As a rule, I set up my work presentations myself; I am very reluctant to delegate these stagings and insist on their supervision. This makes travel indispensable. However, as mentioned, with few exceptions my engagements take place only in this country or in German-speaking countries. In earlier years, I could only afford to travel abroad because of invitations from the Goethe Institutes, although of course the question remains open whether those I visited got as much out of my visits as I did. Nevertheless, I am grateful that I was able to travel in this way to Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Budapest, Sofia, Tel Aviv, Izmir, Delhi, Bangalore, São Paulo, Melbourne and Yaoundé (Cameroon). But all these undertakings were not just pleasure trips, but always connected with exhibitions, lectures, workshops and symposia.

When you think back or look forward, what trip would you like to take us on?

I was most impressed by India’s cultural richness, especially in the “Golden Triangle” formed by Delhi, Jaipur and Agra: A collection of unique sights, all of which would have to be rated as Unesco World Heritage Sites if they had the money to equip lobbyists and publicity agents to haul in such titles. However, I was deterred by the misery visible everywhere due to material lacks and disease and the ruthlessness in the behavior of the people due to the caste system, an unbearable, heartbreaking discrepancy between the historical beauties and wonders on the one hand and the horrible reality of life of large parts of the population on the other. To go on sightseeing tours with bare shoes (possibly polished by begging shoeshine boys) seemed impossible to me; I felt out of place and fled the country. I will therefore not take anyone with me as a travel companion and recommend, in the spirit of Pascal, as quoted above, to stay at home and rather travel in the imagination. Already Xavier de Maistre was content (already in 1790) to undertake a “journey around my room”, only within his four walls. This or a rotation around one’s own body axis can be equivalent to a trip around the world. Not the cruising, kilometer-eating (“all-inclusive”) package traveler can become Columbus, but rather the explorer, adventurer and discoverer, who embarks on “trains of thought in imaginary space” (this is what I called an exhibition in 1970). For this I invite you with pleasure; accompany me by considering my works, a hint quite in this sense already gives the sign “Hier 40000 km”.

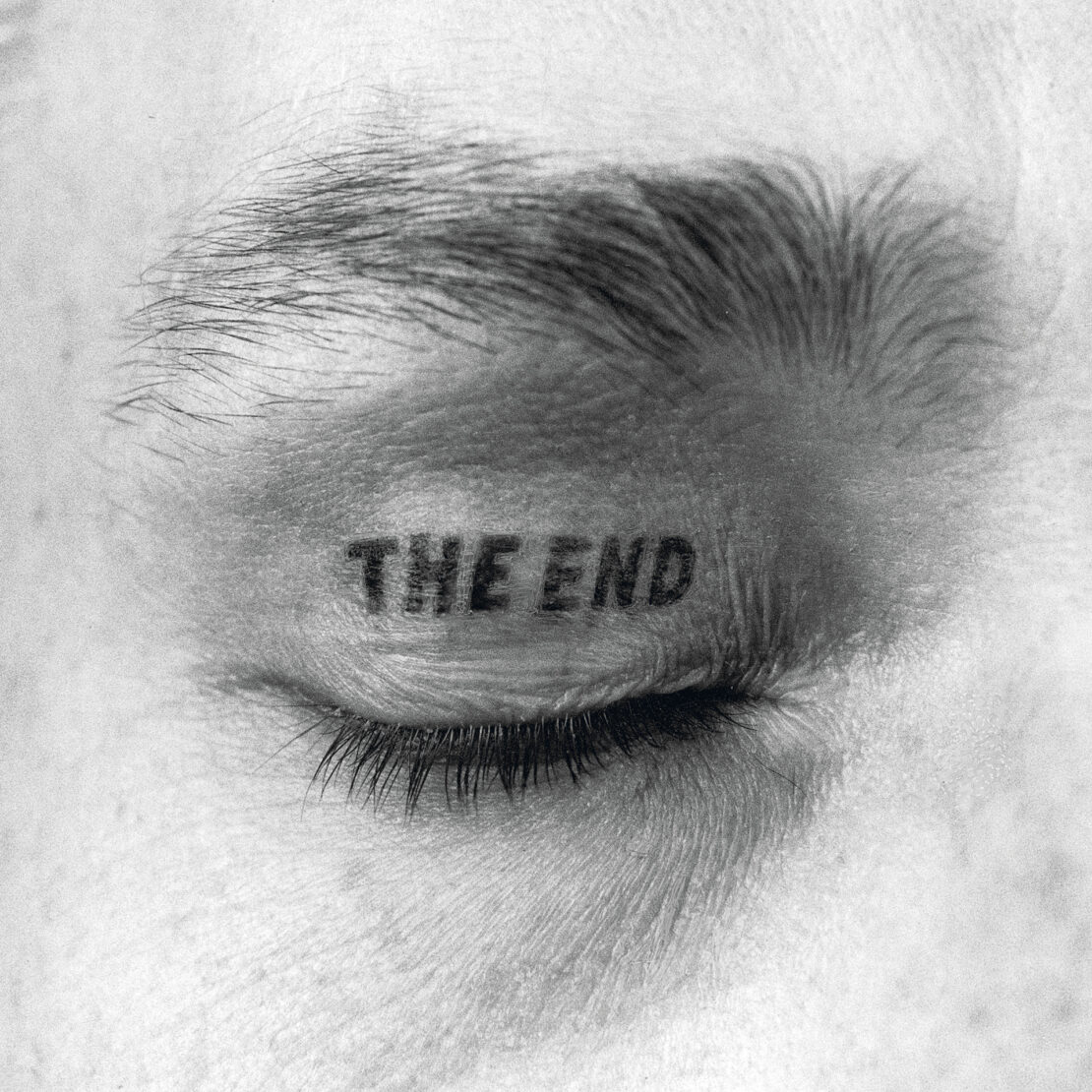

The second work in the exhibition, “THE END”, deals with your own death. How do you deal with it?

Man is probably the only living being who knows about his own mortality, and out of despair in the face of inevitable death he has devised the most absurd and dubious theories, excuses and escape routes. All religions and their promises of forms of survival after death (in heaven or hell), of rebirth and resurrection are fed by this fear of death, but also the desire and the striving for fame, for a survival beyond death through “immortal deeds” and works that may provide knowledge and meaning in life and lasting memory after the death of their creator. Every work, apart from being a source of income, a subject of entertainment and instruction, or a means to show off, also always has a souvenir character; this applies to the only supposedly eternal pyramids of the pharaohs as well as to the only seemingly ephemeral improvisations of a contemporary musician. For all these reasons, I have thematized my mortality and transience several times and early on, for example with my gravestone, whose epitaph reads: “Always remember to forget me!” (1969), as well as with my grave, inaugurated in 1992, on Harry Kramer’s “Artist’s Necropolis” in Kassel, which, as an upside-down life-size hollow-body cast of my body embedded in the earth, is both a work of art and a monument (in this case rather an anti-monument, since it does not nobilize monumentally and upright, but rather makes itself invisible as an empty space) and thus demands double respect. The cemetery visitor is prompted in the act of viewing to lower his head, his gaze, to look down in a mourning attitude and to see through the glass pane cover into the dark negative of my body, into which one day my ashes will be entered. Here everything soon comes together: A contemporary-period sculpture, a permanent site of remembrance designed by the interred himself, and also “the artist is present” in his mortal remains. Finally, the eyelid tattoo, executed in 1981, is derived from the end shots of feature films: When I finally close my eyes one day, my eyelids lowering like a film curtain, my “life film” thus coming to an end and I start my last journey, I say goodbye to life and my audience with these then really last words, with laughing and crying eyes at the same time. Perhaps, in the end, the most essential meaning of all travel, of the tailing off into the distance, is to see one’s own, the near, the here and now with new or – as one says – different eyes after returning from a foreign land.

Biography

- * 1940 in Berlin

- Self-proclaimed total artist

- Lives and works in Hannover

Exhibition

Bon Voyage!

Reisen in der Kunst der Gegenwart

13. November 2020 – 16. May 2021